In Australia, over 7,150 thousand plastic bags go to landfill every minute, and less than 4 per cent of plastic bags are recycled.

Worldwide, governments are trying to tackle the environmental crisis by implementing new policy and regulations such as banning single-use plastic. According to the United Nations (2018), more than 127 countries had adopted restrictions on plastic bags.

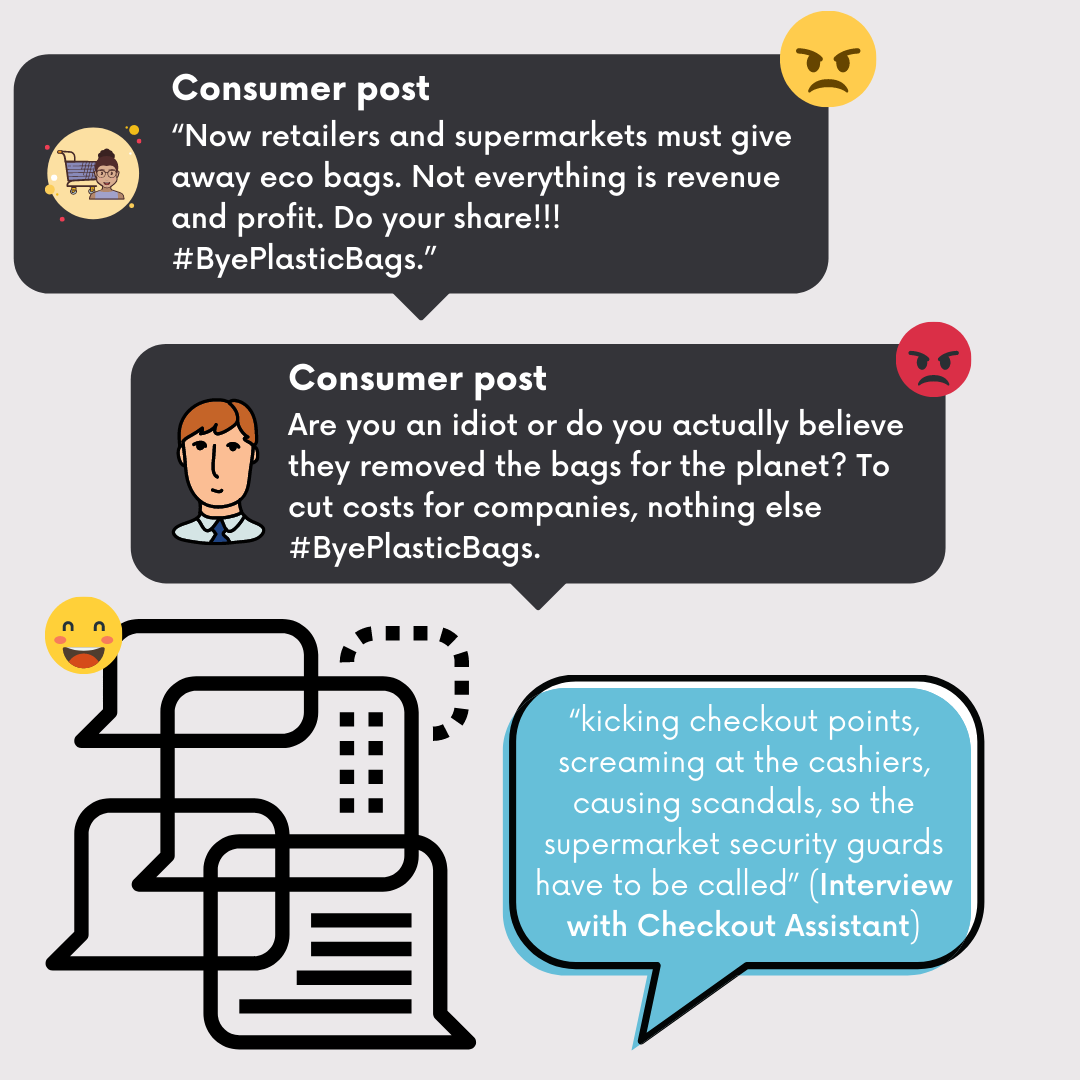

Yet, when plastic bag bans are introduced, governments have been met with significant backlash from consumers and retailers, in what is called a ‘green gap’ – when people have positive attitudes towards sustainability but resist the intervention.

So, what is the solution?

Researchers at The University of Queensland (UQ) Business School conducted extensive research on the plastic bag ban in Chile, to understand why interventions of this sort may be met with resistance. They found changing social behaviours collectively, rather than targeting individuals is more effective.

Dr Alison M. Joubert, Dr Claudia Gonzalez-Arcos, and Professor Jörgen Sandberg (pictured from left to right) discuss why we should understand sustainability from a social perspective.

Why did you select Chile as your case study?

Chile was the first South American country to ban the use of plastic bags nationally. Like many other countries, the plastic bag ban seemed like an “easy way” to reduce plastic pollution. Yet, the ban was met with a high level of consumer resistance – in the form of public displays of resentment and other emotions as consumers struggled to accept, adjust to, and support it.

We also chose Chile because there were two government-initiated hashtags – #ChaoBolsasPlasticas [#GoodbyePlasticBags] #Llevatublosa [#Bringyourownbag] – that were widely used to discuss the bans, and so made it easier to track the reactions.

What did you observe when conducting your research?

We discovered that when sustainability interventions aim to change individual behaviours rather than broader practices, they fall short.

Everything we do (e.g. grocery shopping) is not one individual behaviour but a practice made up of: the materials we use for the behaviour (e.g. plastic bags, trolleys and baskets); the skills we have for performing the behaviour (e.g. how to efficiently carry and load groceries into the car) and the meanings we attribute to the behaviour (e.g., plastic bags are convenient). Collectively, this is a shared understanding of how grocery shopping is ‘supposed to go’ and how it fits into our collective lifestyles.

When one of these three components is changed with an intervention (like a plastic bag ban), those impacted must:

- Make sense of the change (e.g. understand how the loss of bags changed shopping).

- Accommodate the change (e.g. bring reusable bags to the store).

- Stabilise the new version of the practice (e.g. continue to shop without plastic bags).

Why do shoppers react so emotionally?

In the case of the plastic bag ban, people not only found it hard to be “good shoppers” after the ban, but they also felt as though they should not be the only ones responsible for the change.

Shoppers experienced unsettling emotions - frustration, anger, shame when they forgot to bring bags, and started to see other practices that also require plastic (e.g. grocery store storage of fruit and vegetables) as potential problems, even though it was not yet part of bans. These tensions made them reluctant to want to adopt the new shopping practice, and so they resisted.

How can your findings from Chile be applied to Australia and our single plastic bag problem?

In Australia, there is still a large focus on banning plastics to drive sustainability. Yet, we have not yet seen a total national implementation of a plastic-bag ban. NSW government has not yet employed a state-wide ban, however, Queensland and other states have moved onto discussions of bans of additional types of plastics.

We should aim to stabilise the “new normal” collectively. Plans for how we move towards a more sustainable and less wasteful way of life should be together; this should not just be on individual consumers.

Instead, a key to reducing consumer resistance to sustainability interventions such as a ban on plastic bags, is to focus on social change rather than individual behaviours.

What outcome do you hope your research will have on government and future policy?

We have seen the same types of challenges being experienced with the mask mandates and other interventions aimed at reducing the spread of COVID-19 as with the plastic bag bans. Having to adapt to the ‘new normal’–shopping without bags or going about your daily life with a mask – can be challenging. What alternatives should be used instead of bags to carry groceries? Which masks are easiest to breathe in and lead to less fogging of glasses? These are just some of the questions that need to be thought about when implementing bans and interventions.

In our paper, we provide guidance for marketers and policymakers on how to design practice-based interventions that reduce consumer resistance at the outset. It also provides recommendations for monitoring resistance once an intervention is implemented and how to adjust accordingly.